When it comes to indoor mold, myths and misconceptions run rampant.

This is particularly true for toxic mold, also known as black mold, which has garnered much attention in recent years, and has become about the closest thing the fungal world has to a Public Enemy #1.

And while we aren’t here to exonerate black mold or tell you that it’s something you should ignore, its outsized notoriety and the misinformation surrounding it present other hazards.

Let’s take a look at what toxic black mold is and get to the truth behind its significance.

Toxic Black Mold: Media Superstar

In our experience, the majority of people who worry about mold in their homes or schools or offices center their concern around toxic black mold. This is not a coincidence.

The dangers of black mold are consistently amplified by media headlines and even industry professionals, so much so that one could be forgiven for incorrectly believing there is only one type of mold growth worthy of concern.

What’s more, this kind of singling-out helps feed the more broad, but equally false narrative, that some types of molds require action while others do not. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Let’s clear the air.

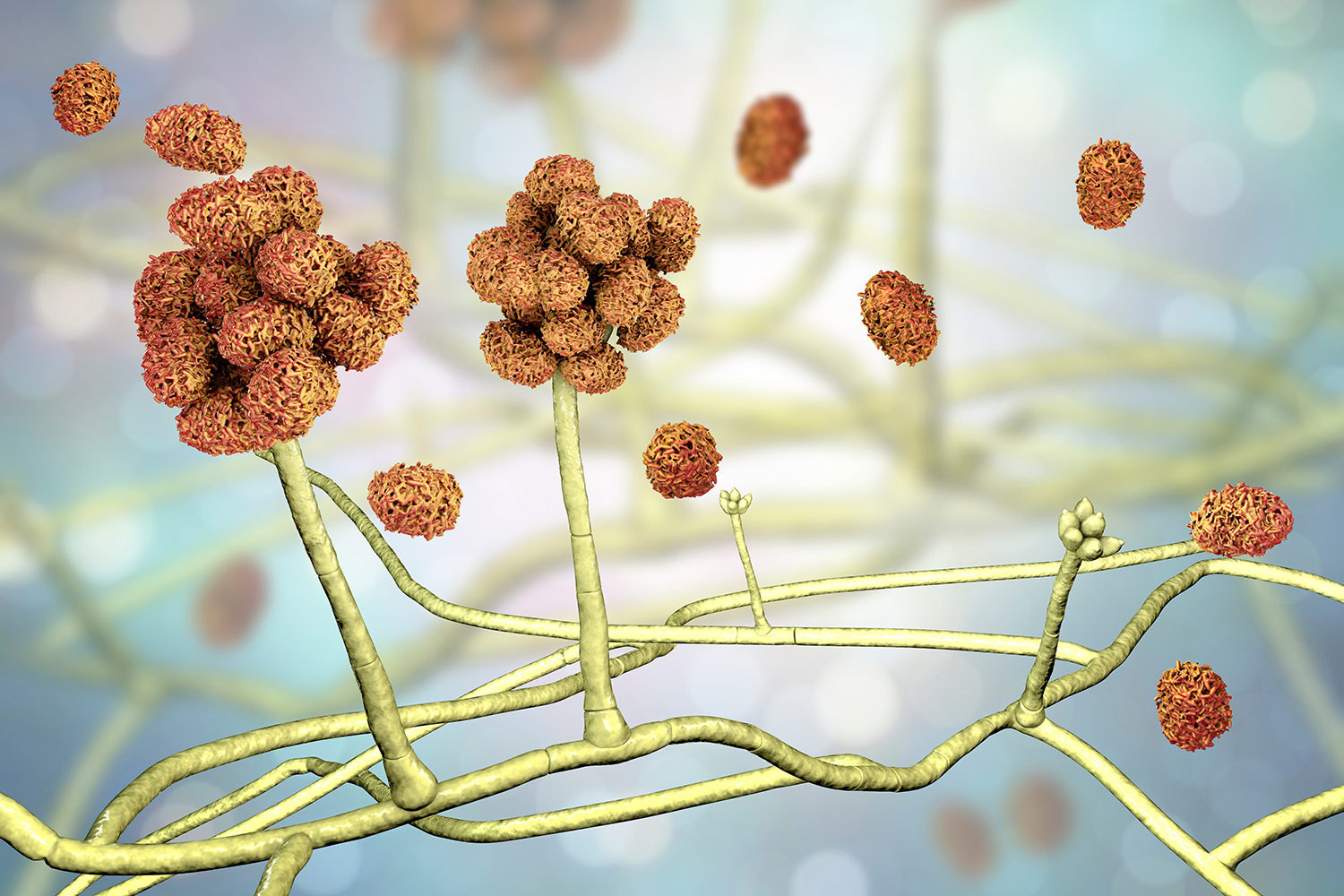

First off, there is no one type of black mold—many molds are black in color. However, when most people refer to toxic black mold, they’re likely referring to a type called Stachybotrys chartarum (S. chartarum), also known as Stachybotrys atra, or “stachy” for short (pronounced: stack-ee). Ironically, even Stachybotrys isn’t always black. It’s often dark green upon close examination.

The reason that Stachybotrys species have been so loudly connected to health hazards is due to research linking mycotoxins from S. chartarum to serious health problems in people who live in contaminated buildings. Although most of the research has been found to be flawed—sometimes deeply flawed—these claims are not baseless.

The Truth About Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are naturally occurring toxins released by some molds, which can cause serious harm. But not in the way the media or most “mold experts” will tell you.

And the hyperfocus on them distracts from the larger concern about mold growth indoors, and from what the presence of Stachybotrys and other molds commonly found in chronically damp buildings actually means.

Mycotoxins are used by molds to compete with other microbes, essentially creating chemical warfare on a microscopic level, with all of us in the crossfire. According to the World Health Organization, the adverse health effects of mycotoxins range from acute poisoning to long-term effects such as immune deficiency and cancer.

Black mold isn’t the only species to release mycotoxins. About a hundred different species are responsible for 300 to 400 compounds recognized as mycotoxins, of which approximately a dozen groups are considered threats to human and animal health.

The fact is, most mycotoxin exposure comes from food, not air. The United Nations and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have long estimated that up to 25% of the global food crop is contaminated with mycotoxins. Now, 25% is certainly nothing to sneeze at, but a 2019 paper, coauthored by a team of Canadian and European researchers, suggests that this may be a vast undercount. Their findings estimate instead that mycotoxins may affect 60-80% of all grains. That’s an incredible number, but it’s a discussion for a different day.

The myopic obsession with mycotoxins presumes they are the primary cause of mold-related illness, which is factually incorrect. Only a small percentage of mold species produce mycotoxins, and those species produce them intermittently under specific circumstances.

Reputable scientists who study these things, like toxicologist Dr. David Krause, founder of HealthCare Consulting and Contracting (HC3), point out that even those molds don’t produce them very much in buildings because the materials they are noshing on, like drywall paper, don’t have enough nutrition to support the metabolically expensive process of producing them, and the conditions in our homes are too comfy!

Mycotoxin production is actually stimulated by extreme temperature swings, especially cold temperatures, which doesn’t often happen in our living spaces, thank goodness.

Volatoxins

On the other hand, all actively growing molds produce compounds known as microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCS) which most people recognize as the musty odor. Long dismissed as a mere aesthetic nuisance—that basement smell—emerging science has found that these chemicals can be neurotoxic and lead to a wide variety of illness. But mVOCs are not classified as mycotoxins despite their toxic effects. Prominent mold researcher, Dr. Joan Bennett at Rutgers University suggests that we should call them “volatoxins,” combining the words volatile and toxins.

Unlike mycotoxins, they readily penetrate walls, and disperse easily into the air, which is one of the reasons that the growing consensus in the academic and research community is that mVOCs are more likely the blame for most mold-related illness.

And since mVOCs are produced by ALL actively growing molds, the species doesn’t matter.

Nor does the color.

What matters is the dampness.

That being said, a very lucrative industry has emerged around mycotoxin testing, cleanup, detoxes, etc., which seems to be causing more harm than good. It’s hard to make sense of it all, even for people who are in the business. The average consumer doesn’t stand a chance. Hence the reason for this piece.

Molds Require Food to Grow

Unfortunately, many modern building materials are an appealing meal for mold. It wasn’t always like this. Contrary to popular opinion, old buildings are not so mold-friendly. Mold won’t grow on plaster, brick, or concrete. Even old-growth lumber is too hard for mold to eat. But in the interest of faster, cheaper construction, we now build our buildings essentially out of mold food. Typical light-frame construction is only a few steps away from paper-mache, and of all the materials mold loves to eat, gypsum wallboard (drywall) is at the top of the list. Even the dimmest of the three little pigs didn’t build their house out of paper, but that’s exactly what we do.

As if this isn’t all bad enough, Danish researcher, Birgette Anderson, found that ALL drywall is pre-contaminated with mold spores, including Stachybotrys, from the time it comes out of the factory.

So, black mold sounds scary. And it is. But not just because of the toxins.

Stachybotrys, and the other toxigenic molds, are certainly of concern, but they are not THE concern. They are clear indicators of a serious, chronic water problem, which is what you should worry about address, first and foremost.

If you test and don’t see Stachybotrys in a building with a water problem, that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t take action. On the contrary. It just means that you may have gotten to it early enough. But given enough time and moisture, in our drywall-laden modern buildings, Stachy will rear its ugly head. It’s almost a guarantee.

Moisture is the Real Problem

Because of the well-publicized stories about people who lived or worked in buildings with Stachybotrys becoming afflicted with scary and debilitating illnesses, many people have a singular focus on this one type of mold. But they are missing the point. These buildings have serious moisture problems. The mold didn’t pop up on its own.

Toxic black mold doesn’t just appear. It takes very specific conditions for Stachybotrys spores to grow into a serious problem, and it doesn’t happen overnight. It often takes weeks, even in optimal conditions for mold growth.

According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Stachybotrys typically grows only on repeatedly wetted materials that contain cellulose—from paper to ceiling tiles and any kind of wood. (In nature, Stachybotrys likes to eat the dead grasses on the side of the road, in gulleys, or along river banks.) It likes a wet-dry cycle, like what you see in a basement that leaks intermittently. The wallboard gets wet and then dries out. And then it gets wet again and dries. Every time the dampness returns, the mold grows bigger and stronger. And it never dies. It just waits. And it can wait for a very long time, longer than you will be alive. So prevention is the name of the game.

Also, Stachybotrys is what’s known as a “late-stage colonizer,” which means that other molds start growing much earlier and more quickly when things get wet. These common molds that show up first are known as “primary colonizers” and they include Penicillium and Aspergillus. There’s also an interim legion of molds that will join the party, aptly known as “secondary colonizers.” All of which is to say that by the time Stachy has started to grow, mold growth has been going on for a while.

Excess moisture or water damage is always the starting point for indoor mold growth, and its presence is a sure indication of a moisture problem in a building. That’s the real issue: A mold problem is a moisture problem. Plain and simple.

So, prevention is the best medicine. Keep things clean and dry. But we live on a water planet. And with the current trends in weather, we are likely to see a lot more floods and unwelcome dampness, so when it happens—and it will—act immediately. The first round of colonization can occur in as little as 24-48 hours, which is why we always say, If you see something, smell something or feel something, do something. And do it quickly.