As the holidays approach and the decorations start coming out of the attic, you may be surprised to discover you’ve got a mold problem.

In the attic? How’d that happen?

An attic is the least actively used space in most homes. Not only is it out of sight and therefore out of mind, but it’s usually pretty inhospitable—scorching hot in the summer and brutally cold in the winter. These extremes, in fact, are a big reason why some attics get moldy.

Here’s the thing: For a mold problem to develop, you have to have excess moisture. No water = no mold. That means mold will not grow in a dry, well-ventilated attic. So what causes moisture to accumulate in an attic? A ventilation problem. It’s really that simple. What’s not so simple? Keeping your attic dry and properly ventilated.

Moisture

People indoors generate significant humidity simply through the mechanisms of daily. Respiration (breathing), transpiration (sweating), cooking, bathing, cleaning, and numerous other activities all pump water into the air. Even having lots of houseplants can add a significant amount of humidity. Damp basements and crawlspaces are big offenders. As are un- or misused dryer vents and improperly installed bathroom exhaust fans.

Here’s where I throw you a curve ball. Most people think it has to be warm and wet for mold to grow, and while that’s partially true, certain molds are able to grow in very low temperatures, though they still require moisture. Ever seen black mold growing on the gasket around a refrigerator? This is usually a common mold called Cladosporium. It doesn’t mind the cold so much. It also has a tendency to grow in attics where there’s a moisture trap. But here’s the key: most mold problems in attics are a wintertime phenomenon, not a summertime one. Counterintuitive but true.

As we all remember from eighth-grade science class, warm air rises in a building. In a case where there’s a lot of moisture in that warm air, and it eventually finds its way into a cold attic, the water in the air will bead up on the cold interior surfaces of the roof, as it would on a glass of iced tea on a hot summer day. During really cold periods, this condensation will actually freeze, making some attics an unintended winter wonderland.

In such circumstances, the exposed nails will transform into icicles overnight, and when the sun comes up, the roof warms and melts the icicles, causing them to drip rusty water droplets onto the floor. This cycle of moisture accumulation on the dusty wooden surfaces of the attic is enough to create an environment conducive to mold growth. Sometimes this takes decades, sometimes only one season. Depending on the severity of the problem, the damage can range from some minor surface mold, which can be easily cleaned, to complete rot and degradation of the sheathing, requiring a new roof. Not fun and certainly not cheap.

Ventilation

Contrary to what you may think, an attic fan is far from sufficient for effective ventilation. That’s because they are designed to operate during the summer to remove excess heat. Also, the vents on opposite ends of many attics, called gable vents, do nothing. They are worthless for the purpose of moisture control. I’ve seen homeowners try every sort of shortcut possible to avoid doing what really needs to be done, but the fact is, there’s only one flawless solution: natural ventilation with ridge and soffit vents.

So, what is natural ventilation?

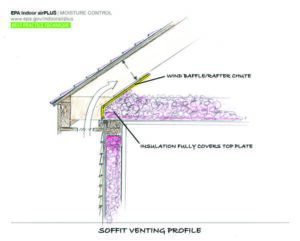

When warm, moist air rises, a well-ventilated attic will allow it to escape through the peak of the roof, via something called a ridge vent. In order to make up for the air escaping through the peak, supplemental air needs to come from outside, but in a very specific way, from a very specific place: the eaves through soffit vents. When this happens — when warm, moist air escapes through the attic peak, rather than being trapped, and the vents in the eaves allow air to come in from outside — the surface temperature of the inside of the roof stays closer to that of the outside of the roof. This prevents condensation in the wintertime and also helps keep the roof cooler in the summer, extending the life of asphalt shingles.

No fans. Nothing to remember to do. It occurs naturally and flawlessly, but here’s the key: The ridge and soffit vents have to be continuous and integrated. In other words, they have to go from one end of the roof to the other end, and they won’t work without each other. Some building codes require new roofs to have ridge vents, but those are essentially useless without soffit vents.

There is a specific amount of ventilation needed for every attic. Owens Corning has an interesting online tool to perform the calculation. Very helpful if you plan on making any changes.

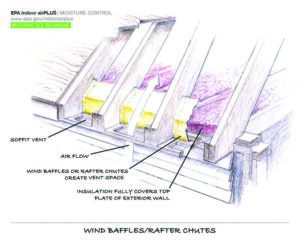

Another crucial element of proper attic ventilation is making sure the vents in the soffits are not blocked by insulation. (See figures 1 & 2.) Many a weekend warrior will install new insulation in the attic to bring down the utility bill, stuffing every bit of insulation possible into the far corners of the attic, including the eaves, and inadvertently blocking the vents. This will render a functional natural ventilation system worthless. Hundreds of dollars in annual savings can eventually become thousands of dollars in mold remediation.

Another common mistake is venting bathroom exhaust fans into the attic instead of through the roof to the outside. When doing bathroom renovations, don’t make this mistake. It’s a costly one. Similarly, the absence of an exhaust fan in a bathroom used for bathing sends a ton of water into an attic. Get a fan installed and use it every time you shower or take a bath. Some people connect the bathroom light switch to the exhaust fan so that they know their kids will use it without thinking about it. Works like a charm.

What To Do

If you believe you have a mold issue in your attic, the first thing you should do is engage a professional who specializes in diagnosing mold and moisture problems. They will track down the moisture source, or sources, assess the extent of the damage, and determine where the ventilation failed and what needs to be done to correct it.

In all cases where a visible mold problem exceeds 10 square feet, the US EPA recommends you use a professional to clean it up.

(A word of caution here: You should never hire a company that performs both diagnostics/testing and remediation. This is a blatant conflict of interest since they will often be testing and inspecting their own work. In fact, some states have even made it illegal to do both.)

If the attic sheathing has not been damaged to the point where it is delaminating and losing its structural integrity, you can usually get away with surface cleaning. In this case, a qualified professional mold remediation firm would isolate the attic from the rest of the house (as described in the IICRC S520 Mold Remediation Standard), bag and remove all insulation, and then clean all exposed surfaces with HEPA vacuums and damp wipes.

Afterward, before the payment is made, the contractor should submit themself to a third-party clearance inspection where samples are collected for analysis to ensure that the job is complete. Also, the inspector should look to see that the appropriate repairs have been made, including the installation of requisite ventilation. After the inspector gives the green light, the insulation can be replaced. Do yourself a favor and get the formaldehyde-free insulation. And make sure not to block the vents in the eaves!

If, on the other hand, the attic sheathing has deteriorated and the plywood has started to delaminate, you will need to replace the roof. I know this is bad news, but it’s the truth. Once that’s done, then you can proceed with the process described above. Or you can initiate the cleaning of rafters and removal of insulation with the roof off, which makes a lot of sense, but it’ll require coordination between the roofing contractor, the mold remediation firm, and Mother Nature. Not always an easy feat. Regardless, make sure the roofer understands what continuous ridge and soffit ventilation are all about and that they install them that way. And make sure all of your exhaust fan vents are directed through the roof to the outdoors.

You may not care much about your attic now, but that’ll change quickly when an out-of-control mold issue starts hammering your wallet or becomes an obstacle to selling your home. Turning a blind eye won’t do you any favors. Proper ventilation will.