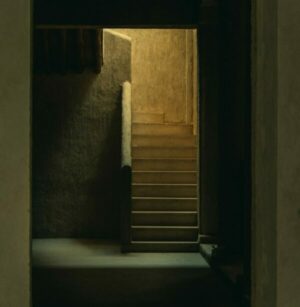

We’ve all smelled it. A friend’s apartment, a hotel room, the home you grew up in, maybe where you are right now. It’s discussed in hushed tones by some, ignored by most, and hated universally by moms.

The basement smell.

This musty odor, though unpleasant, is often overlooked despite being widespread. Many homeowners and renters see it as a minor yet inevitable nuisance. To some, it recalls memories of a grandparent’s basement or a childhood cabin in the woods.

“A home you own,” one might imagine the ad saying, “complete with a two-car garage, ample cabinet space, and a cave-like basement where the kids can play out of sight!”

The smelly basement. An odorous slice of the American Dream. You’ve arrived.

But there is plenty of evidence now suggesting that the musty smell so often associated with basements, vacant homes, and hotel rooms, is anything but harmless or something to ignore.

Expanding Our Understanding

It’s long been known that this malodorous microbial clue can trigger asthma attacks, allergic reactions, headaches, nausea, dizziness and fatigue, but a number of studies have shown that it can actually cause asthma in kids and adults. In fact, early exposure to the musty odor is a leading predictor of asthma later in life, behind maternal smoking. Yikes.

My childhood home made me sick enough that I was falsely diagnosed with cystic fibrosis at four. What I was actually suffering from was asthma compounded by pneumonia, and allergies to nearly everything, all of which were resolved when I moved out of that musty home in the wake of my parents’ divorce. And I had the double whammy. My parents both smoked, too.

But things get really interesting when one looks outside of the obvious threat of respiratory disease.

In 2008, Brown University conducted a large study on household mold, involving some 6,000 participants. What they found was shocking: a strong connection between damp, moldy homes and depression.

This caught my attention, because, although after the divorce I moved out and got better, my mother kept the house, and within two years she took her own life.

Mental health is complex, though, and she was also an alcoholic, so it’s impossible to draw definitive conclusions. But could the mold have played a large part? I say yes.

So of course when I met Dr. Joan Bennett at Rutgers University, and she began to tell me about fruit flies that had become depressed in some of her mold experiments, she had my rapt attention.

The Perfect Storm

In the late summer of 2005, the New Orleans home of fungal geneticist Joan Bennett was ravaged by flooding from Hurricane Katrina, a storm that caused the city’s levies to fail and created a humanitarian crisis that gripped the nation. Bennett and her husband, like thousands of other residents, fled the city, leaving most of their possessions at the mercy of the storm. When they finally returned, mold growth had completely taken over their home and produced such a sickening stench that Bennett felt physically ill.

Bennett was aware of “the sick building syndrome” — a term used to categorize a group of non-specific symptoms like fatigue, respiratory distress, skin problems, eye irritation, mental disturbances, and others that tend to dissipate when the affected person is elsewhere — and though some scientists had linked the syndrome to damp indoor environments before Katrina (it’s sometimes called “damp building syndrome”), Bennett had given it little thought.

Ever curious, the questions her moldy home raised — specifically, why was the smell in her home making her feel so sick? — eventually led Bennett to focus all her professional efforts on studying microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs). Could these tiny carbon compounds emitted by mold, in and of themself be toxic?

“Like everyone, I was familiar with the smell of damp basements, attics, and other places where microbial life grows in enclosed spaces,” wrote Bennett in a 2015 research paper, called Silver Linings, which she penned in memoir style. “But nothing had prepared me for the intensity of the odor in our flooded home. The stench was so strong that it didn’t really smell like mold – it just smelled horribly funky and powerfully sickening.”

Importantly, she was wearing N95 respiratory protection, the kind we all became familiar with due to Covid, and similar to the kind of filters found in HEPA air cleaners, which capture particles like dust, spores and pollen, along with the mycotoxins which often hitch a ride. But they do not remove or capture gaseous pollutants like VOCs and mVOCs which slip right through. Respirators and air purifiers that are able to protect against these chemicals contain activated carbon filters too.

Bennett’s research, which she conducted at Rutgers after resigning from her faculty position at Tulane University, ultimately found strong evidence that the compounds emitted by mold, which she coined “volatoxins,” can be neurotoxic, meaning they impact brain function.

These impacts, Bennett’s work suggested, could trigger a number of neurological issues ranging from headaches and balance difficulty to Parkinson’s disease-like symptoms. Her research even raised concerns that certain mVOCs may cause DNA damage.

Bennett’s work, though short of producing definitive answers at the time, helped set the stage for a greater look at the health effects of fungal VOCs, while bolstering preexistence research that linked mVOCs to illness.

Early Detection

One of the most insidious aspects of the musty smell is that it creeps in slowly and precedes any visible evidence of mold growth. You will usually smell it before you see it. But this is a feature, not a bug.

People ask me a lot how they should test for mold, and even though we sell a top-shelf air test kit, I routinely direct them back to their own senses as the first and most important test. Humans possess an exquisite, integrated array of precision sensors. My standard suggestion is this:

If you see something, smell something, or feel something, do something!

It’s not the most poetic slogan or even terribly original, but it’s particularly important with mold because if you detect a whiff of the musty smell, it’s a dead giveaway of something brewing. And mold does one thing better than most: it grows, often within 48 hours of a water event. The more time it grows, the larger the health threat, and the more expensive the remediation bill.

The bottom line is, do not ignore the basement smell—even when you’re not in a basement. That musty smell is an environmental alert accompanied by tangible health implications, spanning from respiratory ailments to potential neurological consequences. Recognizing and addressing its existence is not only prudent but essential. Our senses serve as an early warning system, so when they signal, it’s imperative to take heed.

How long between mailing the air samples and getting results?

Hi Janet – Depends on how quickly they get to the lab. Once the lab receives your samples, your results will be available within three business days.